The project presented below was conducted for the Edwin Way Teal Artists in Residence Program, founded in 2012 by the Connecticut Audubon Society. The program provides writers and visual artists the opportunity to exercise their creative interests at the Society’s Trail Wood Sanctuary in Hampton, CT, the historic home of naturalist and Pulitzer prize-winning author Edwin Way Teale and his wife and collaborator Nellie Donovan Teale.

Selected artists individually enjoy a week of solitude at the 168-acre sanctuary, free to explore its diverse habitats and landscapes. Artists are afforded use of Teale’s personal library and iconic writing cabin, each drawing inspiration from his legacy to create their own unique interpretation of Trail Wood’s essence and mission.

Introduction

Edwin Way Teale celebrated what he described in A Naturalist Buys an Old Farm as “…the familiar that is also the ever-changing,” both at Trail Wood and beyond. In that book and in the subsequent volume, A Walk Through the Year, he described the progression of seasons, the annual renewal and senescence of the life forms around us, and the continual evolution of our environment.

This residency project explores those dynamics. Photographs taken over ten weeks from early May through mid-July, 2021 illustrate the changes observed during that limited period in four Trail Wood habitats that were familiar to Teale – the iconic long lane, the resplendent meadows, the varied wetlands, and the surrounding forest.

Those habitats are profiled individually here. Each section begins with representative photographs depicting gross changes in the character of the subject habitat as spring passed into summer. Transitions are shown in plant biomass and morphology that in turn caused changes in insolation within those environments and in the configuration of the trails whose use by humans and wildlife Teale described.

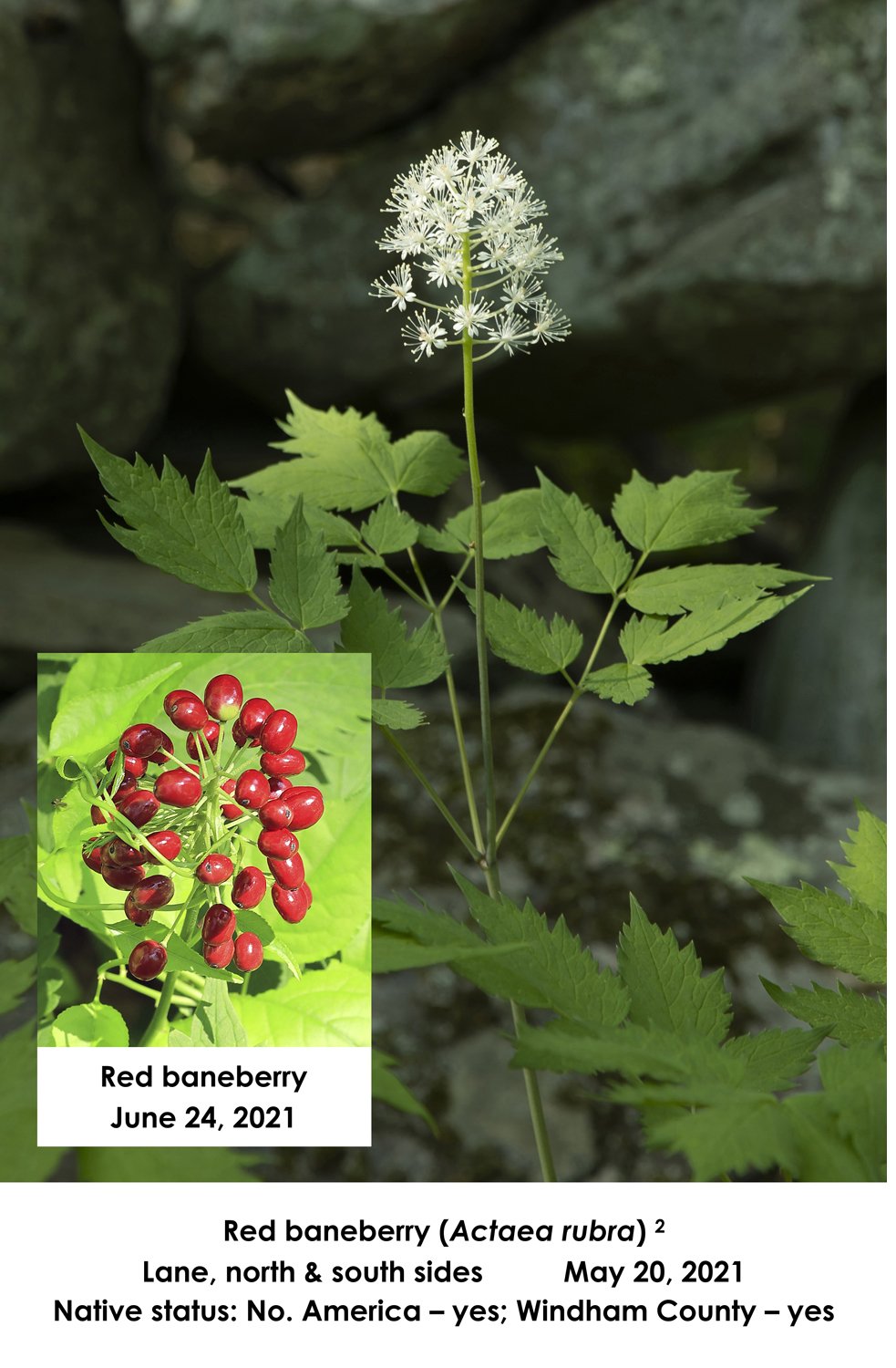

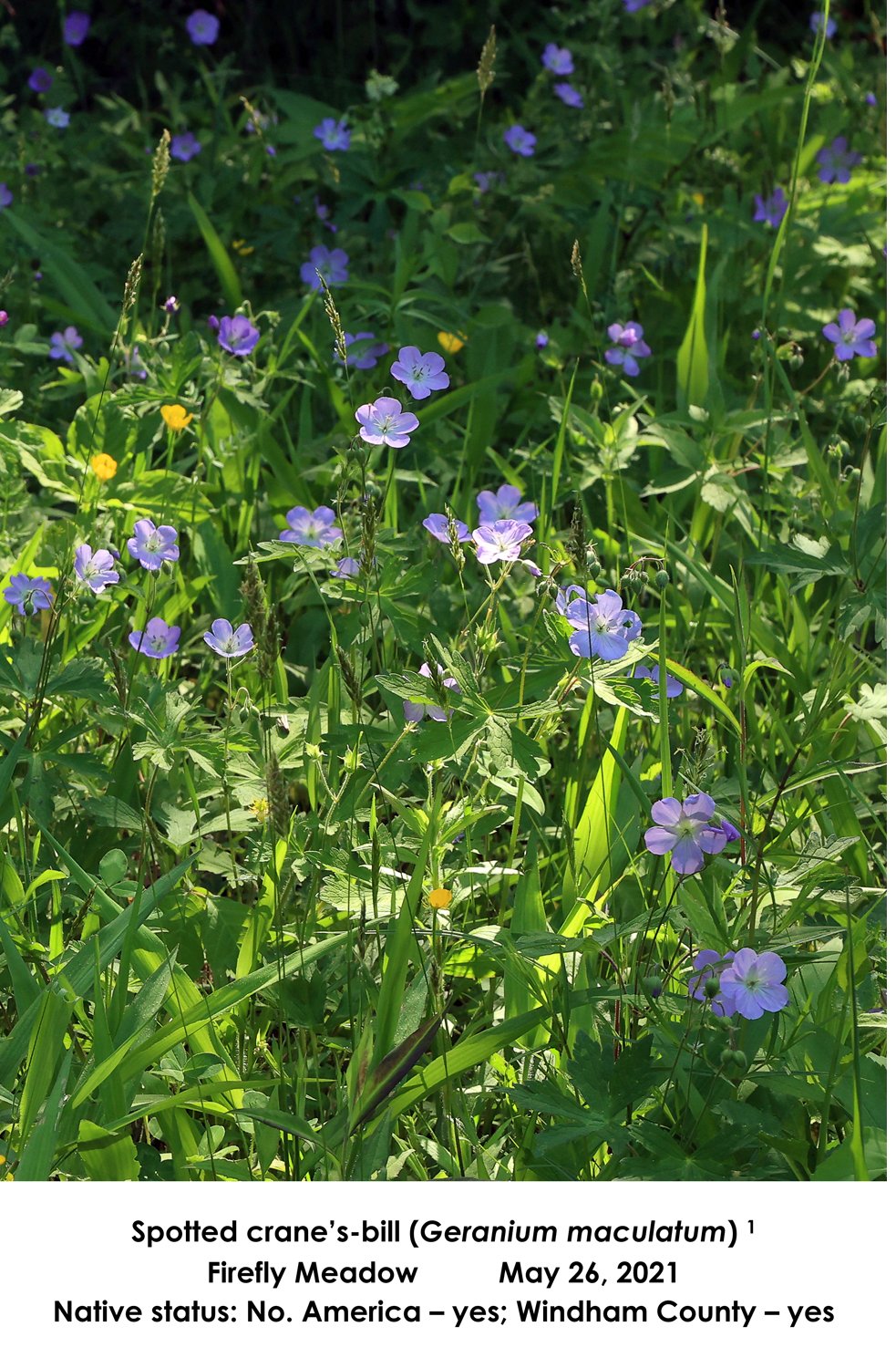

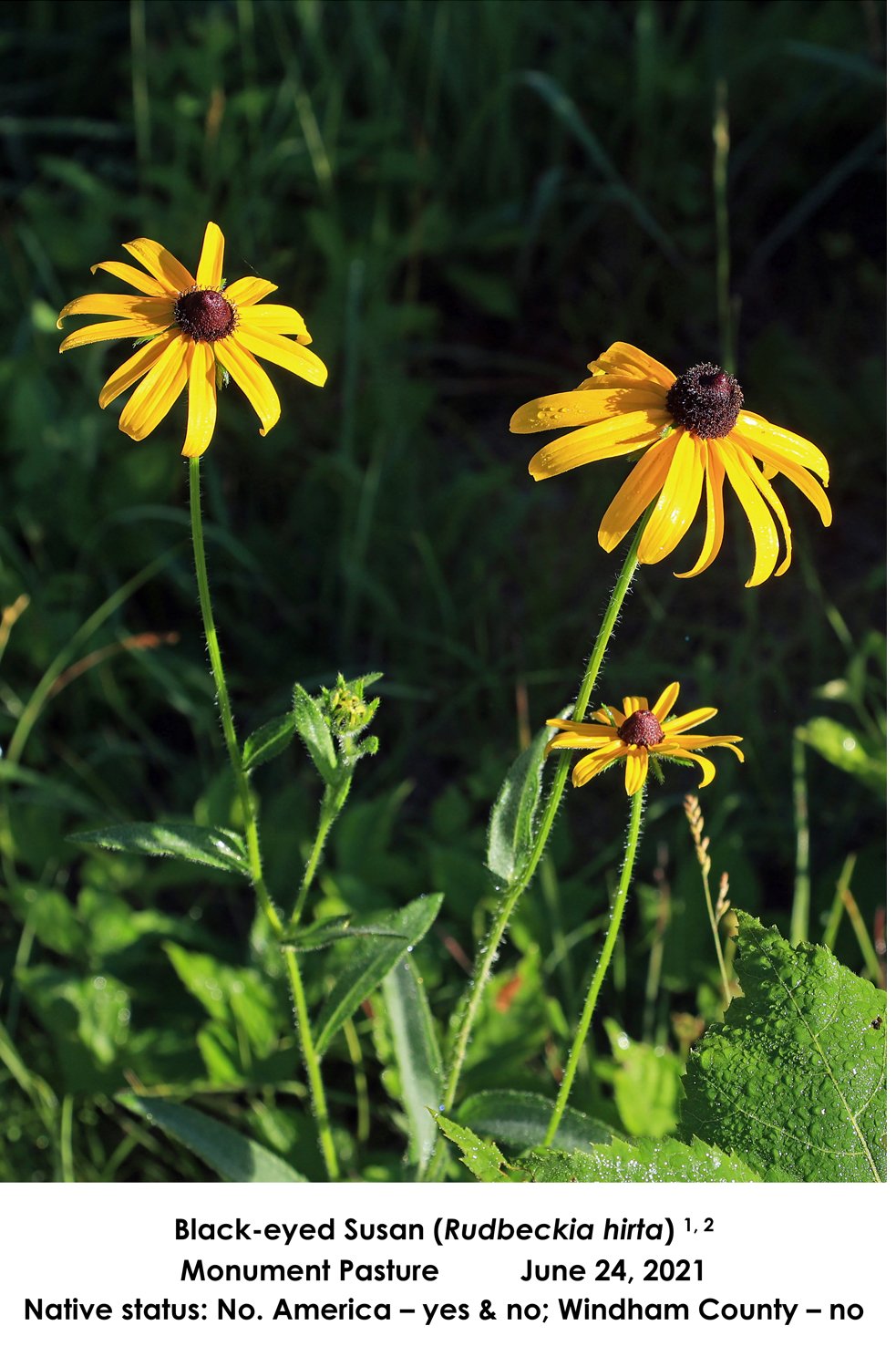

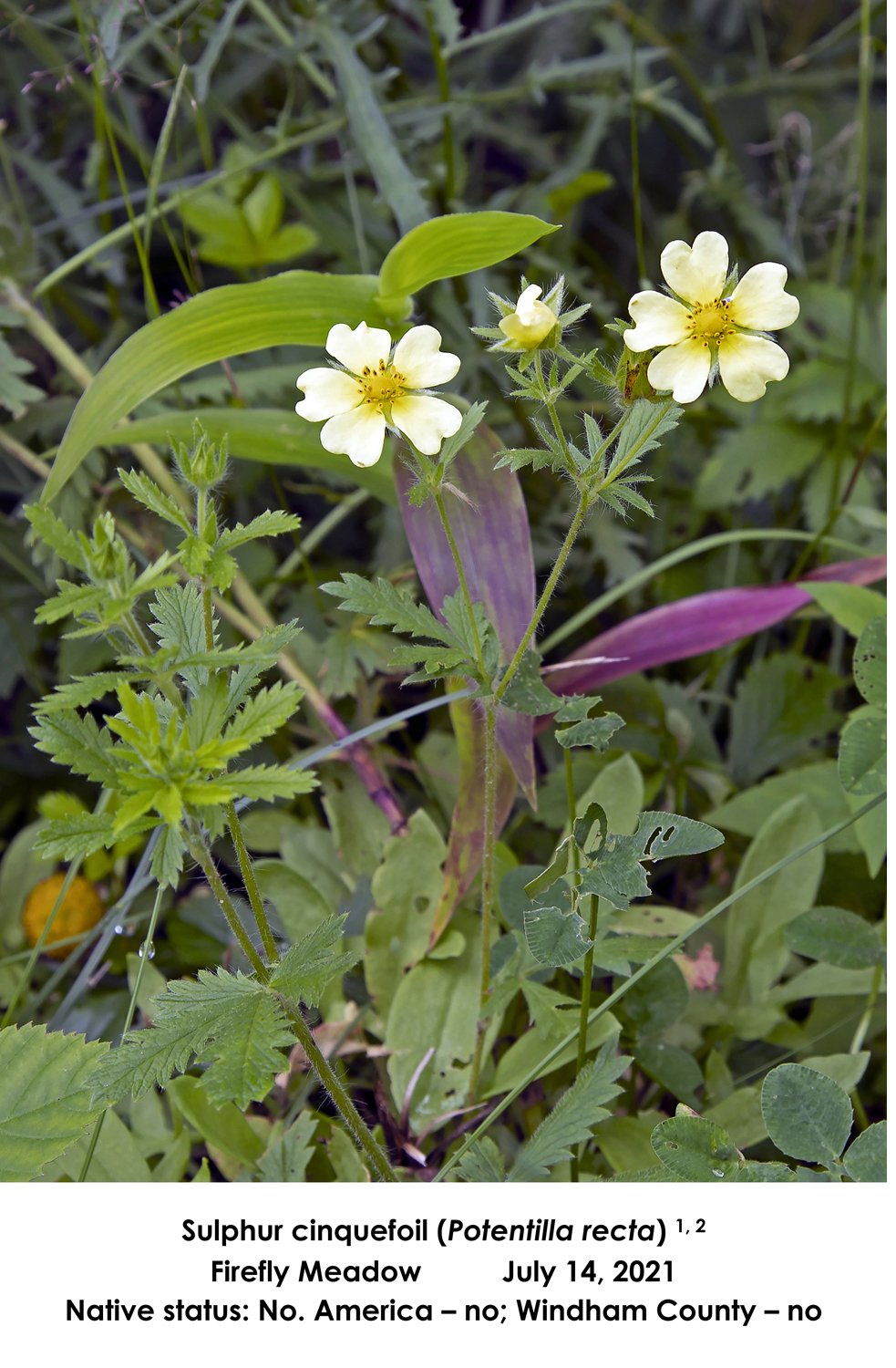

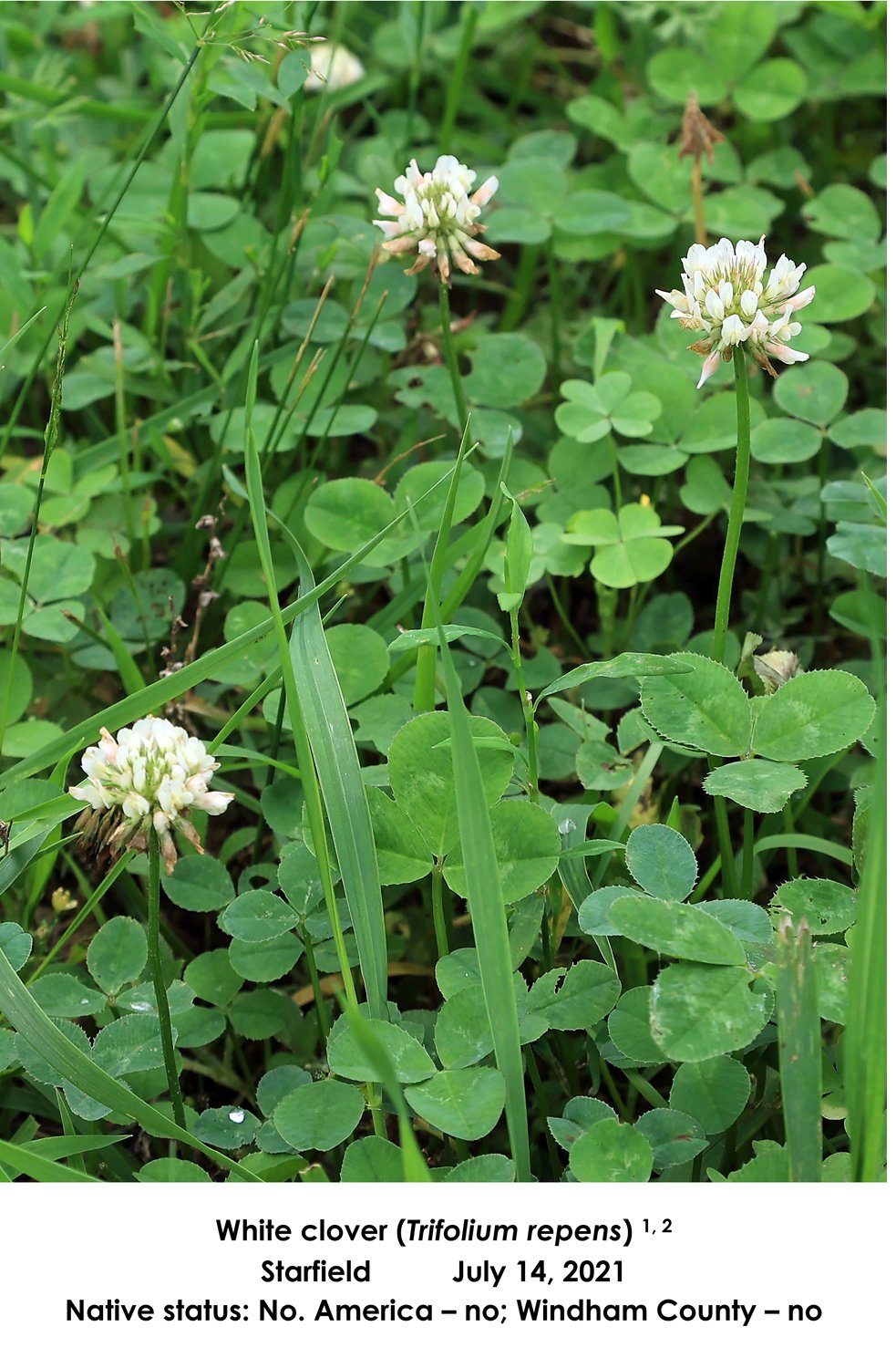

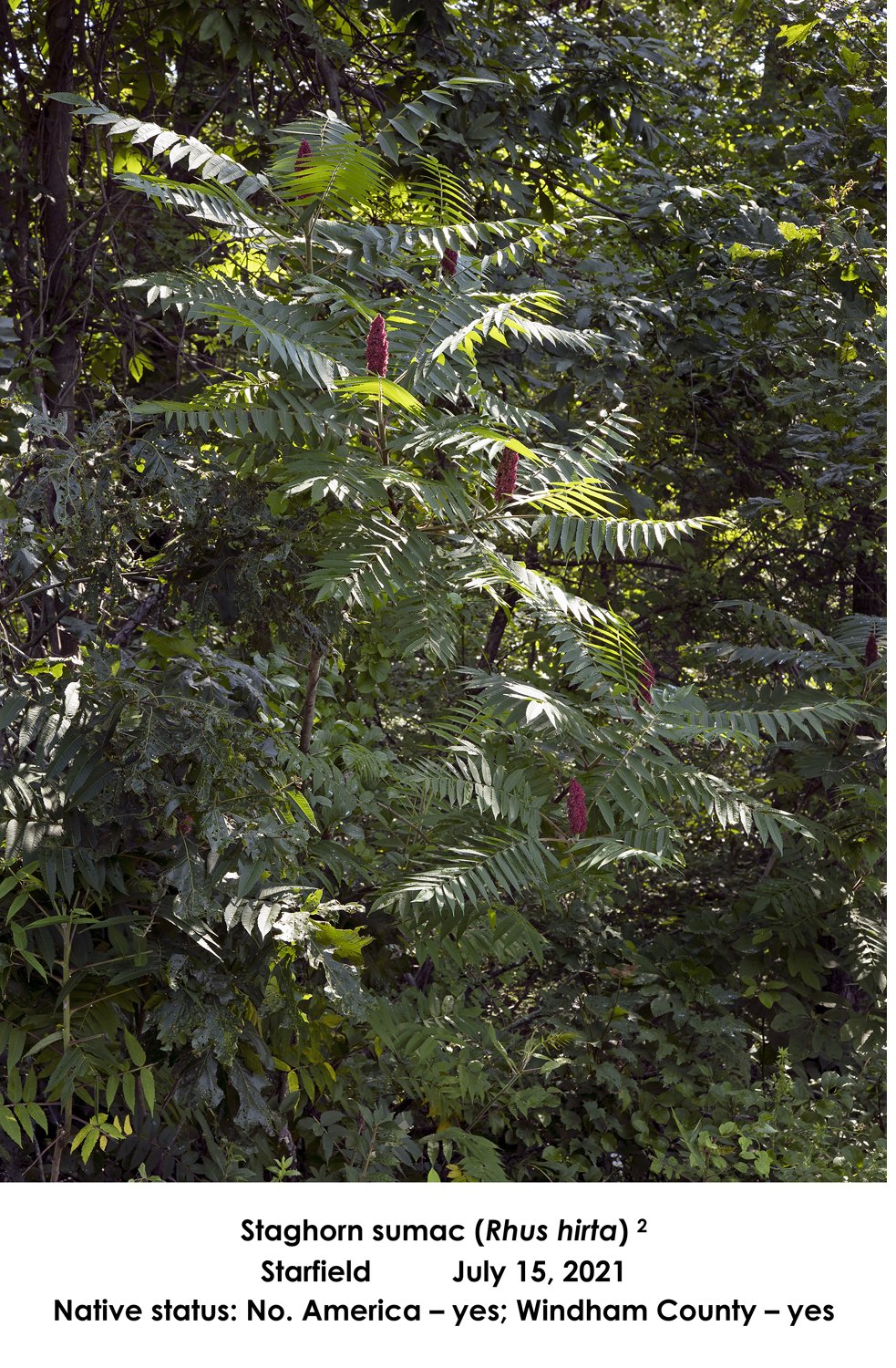

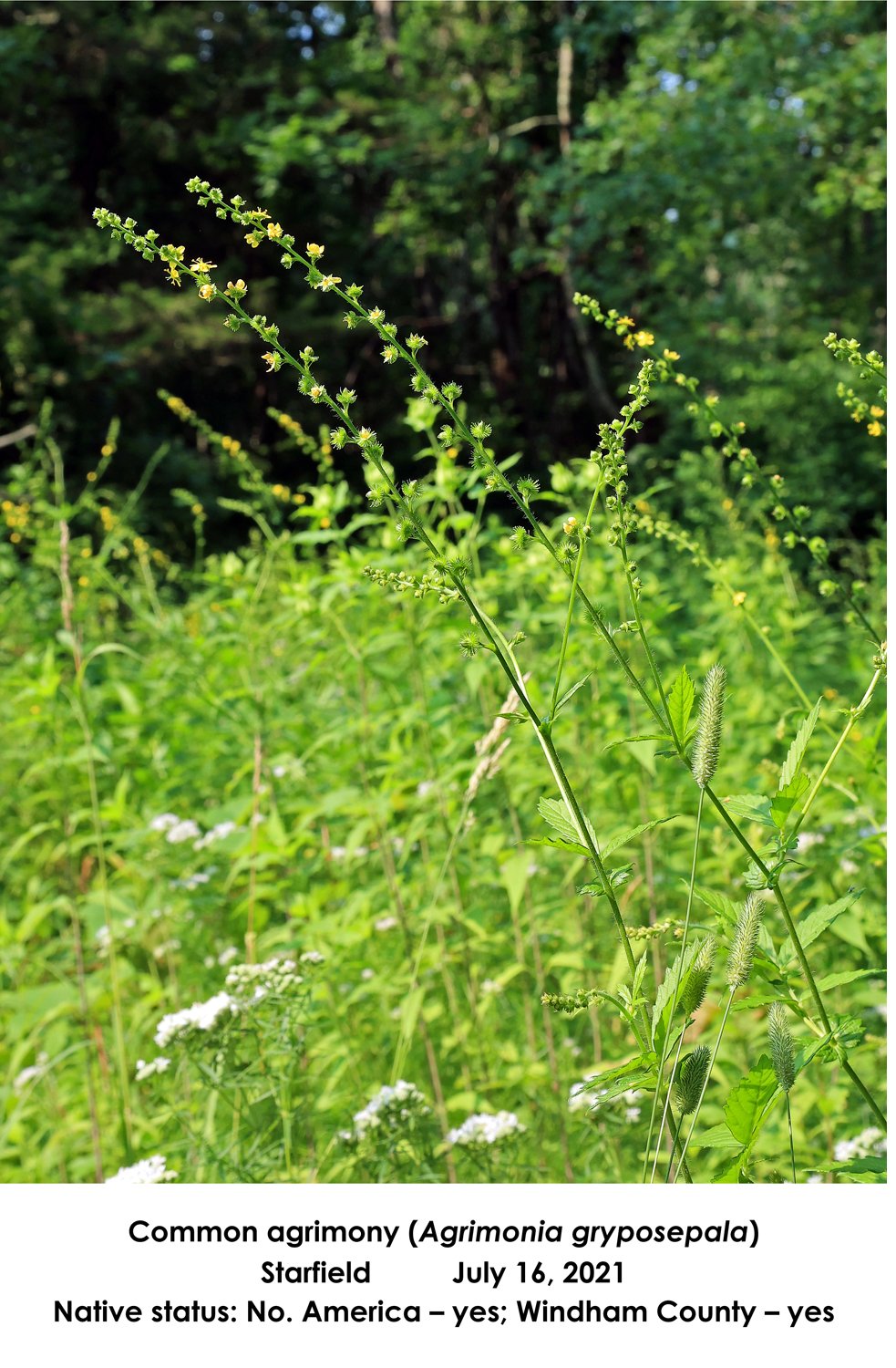

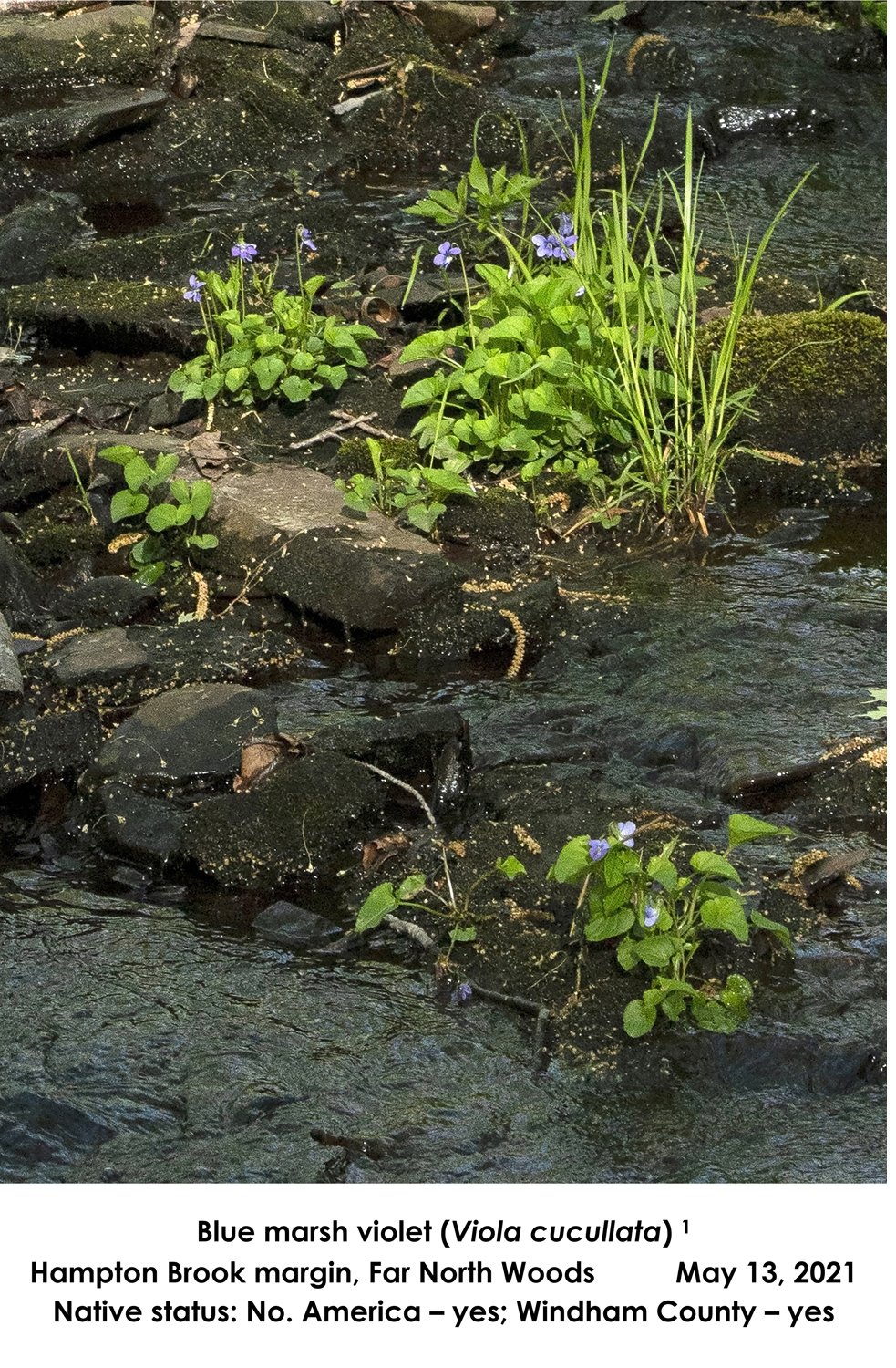

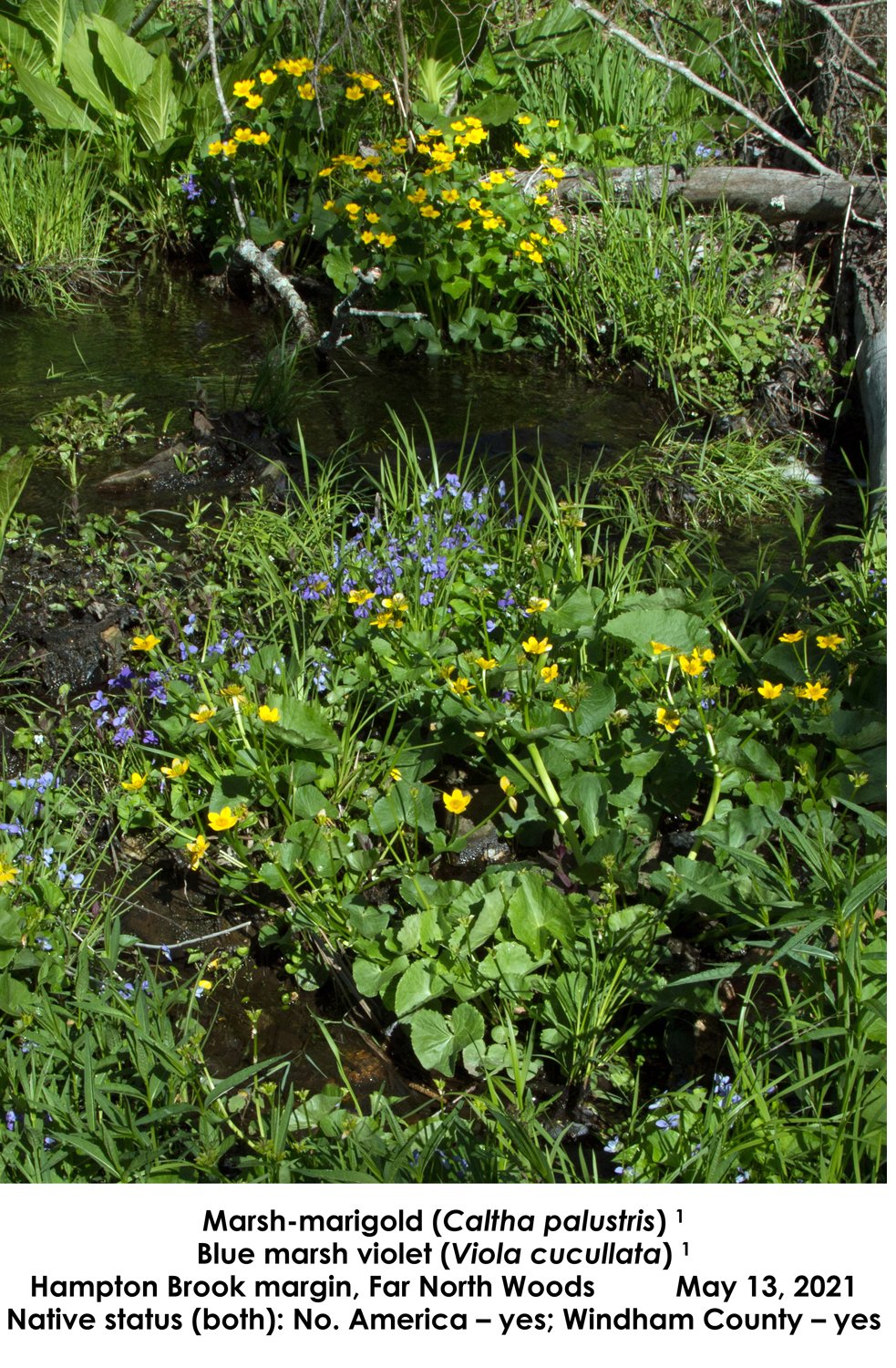

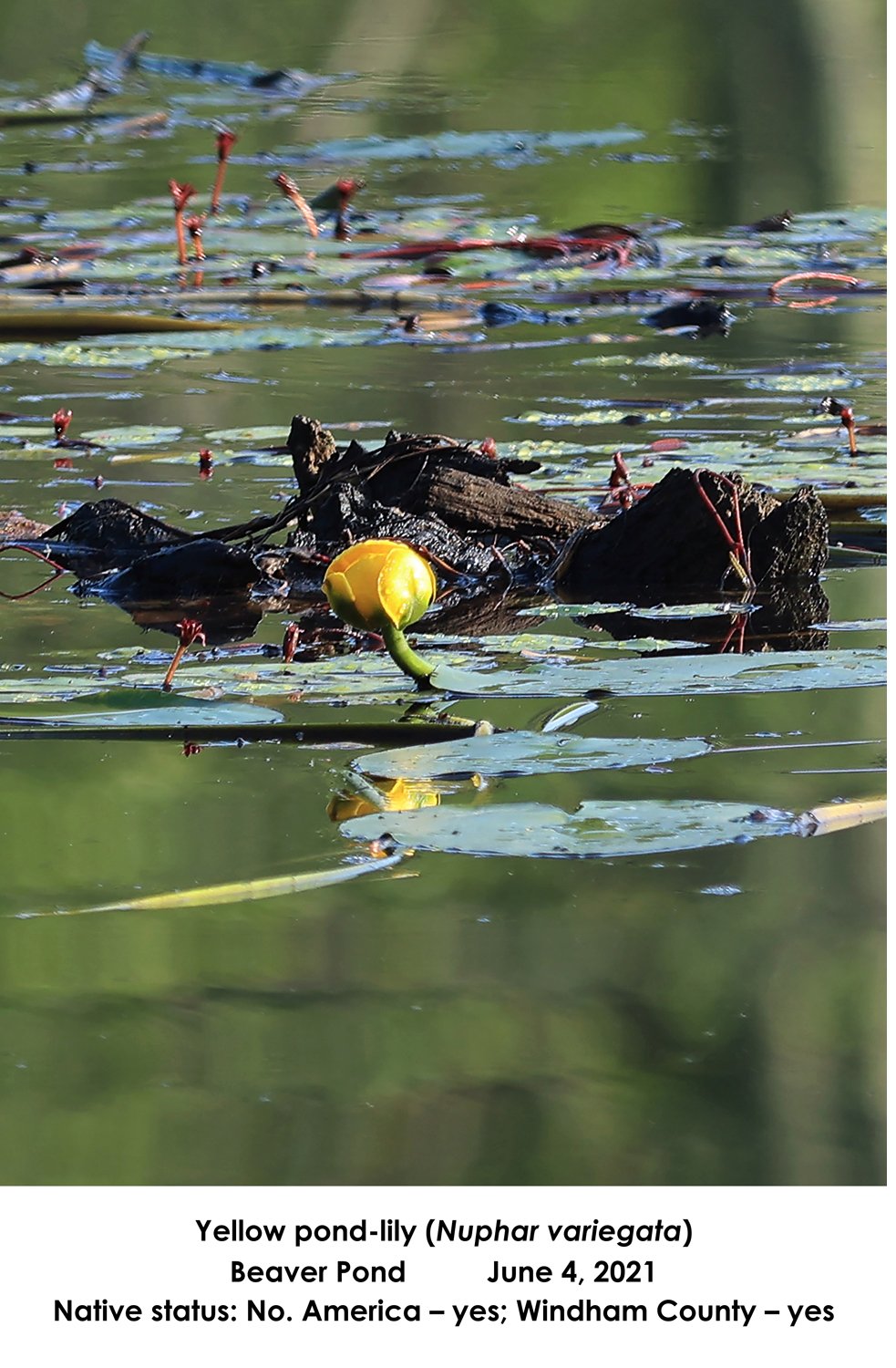

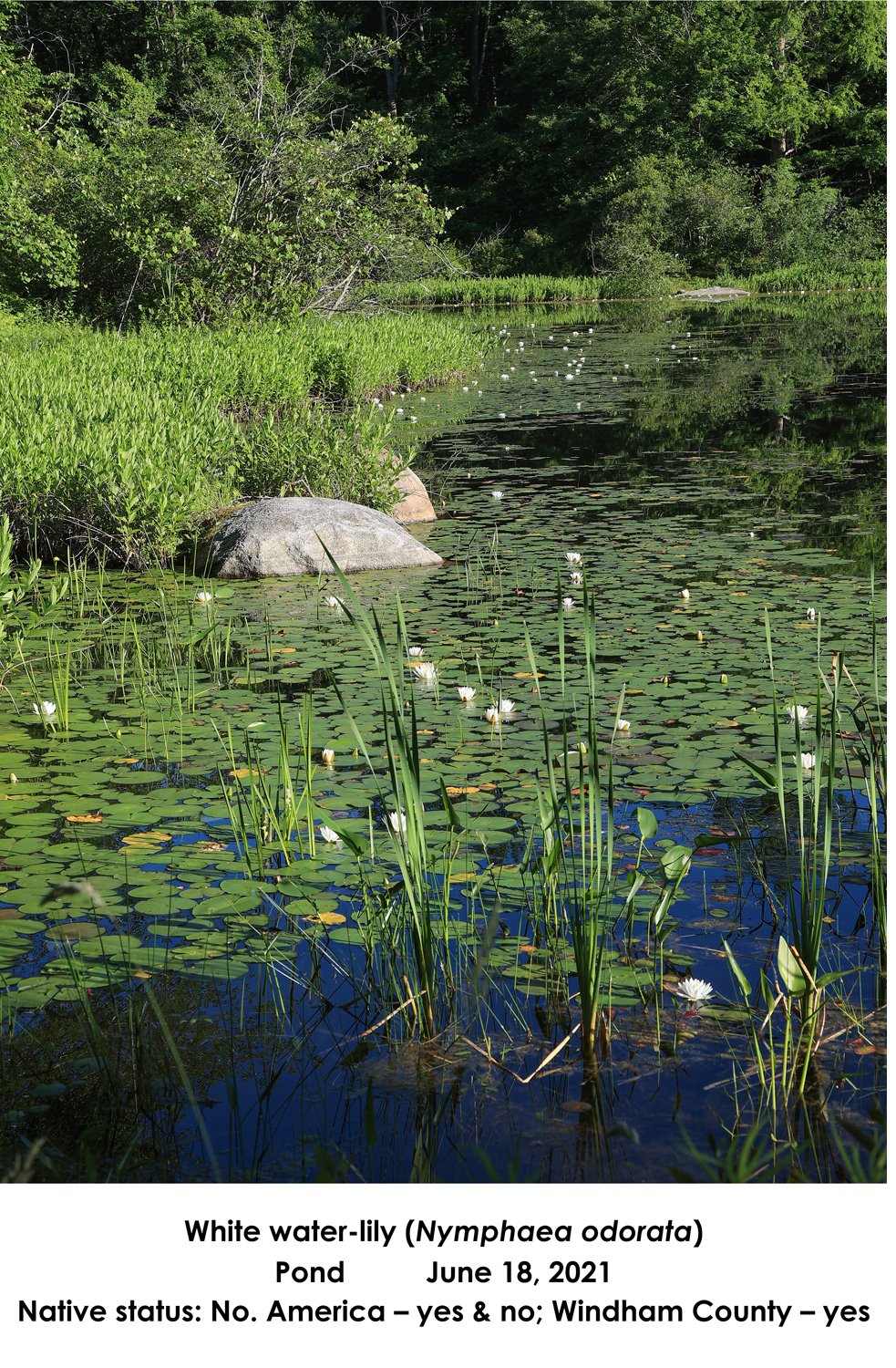

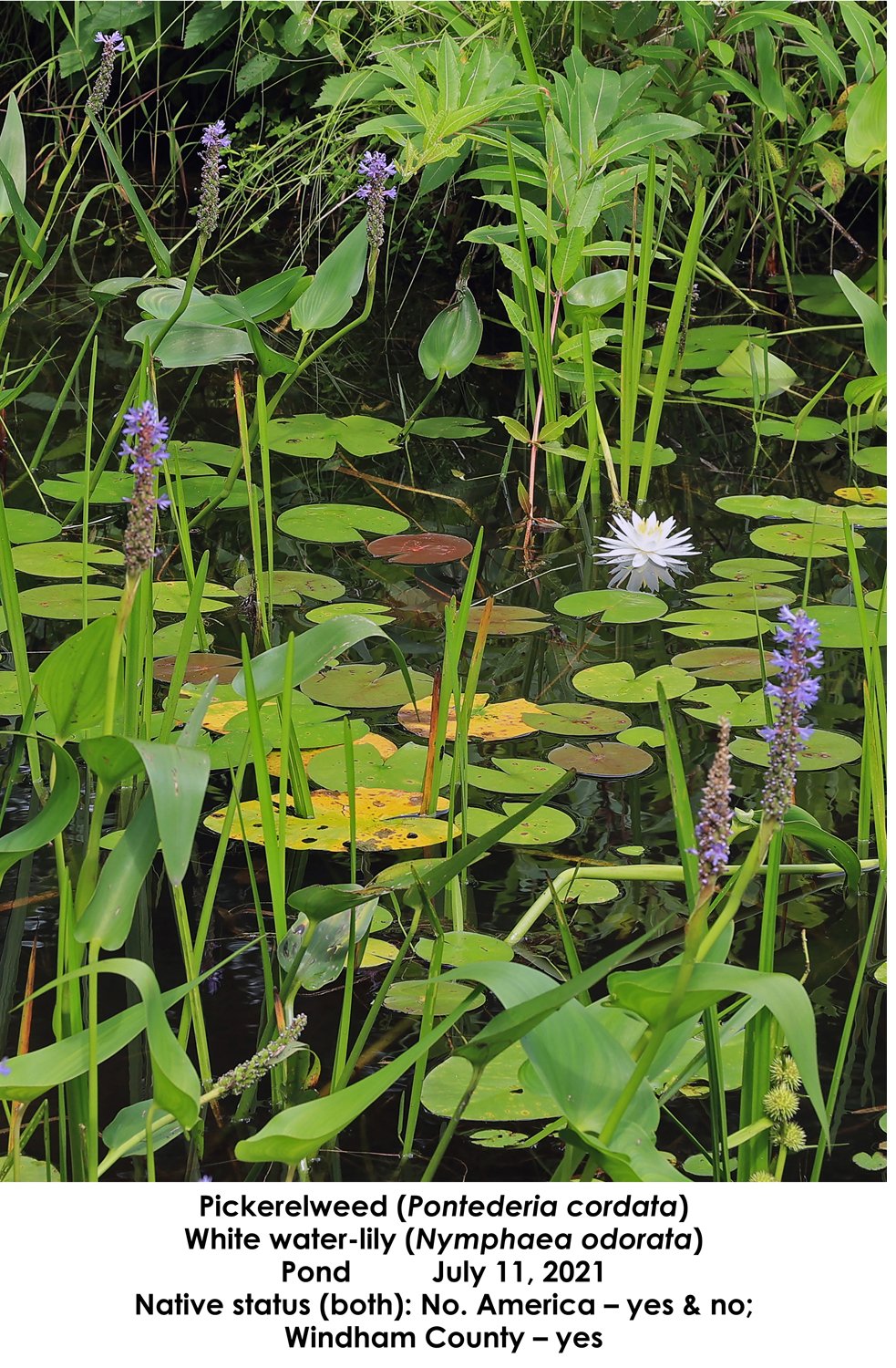

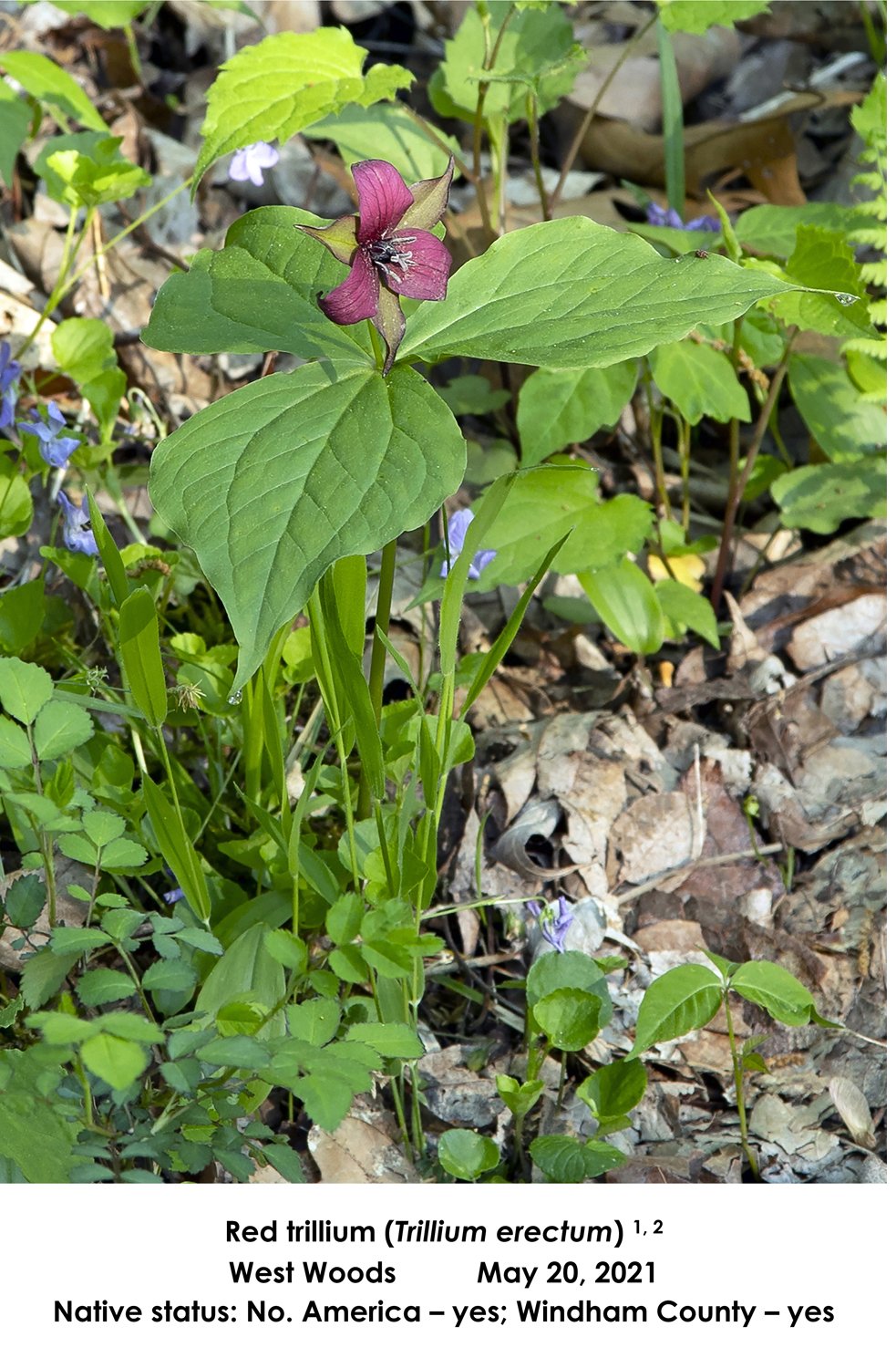

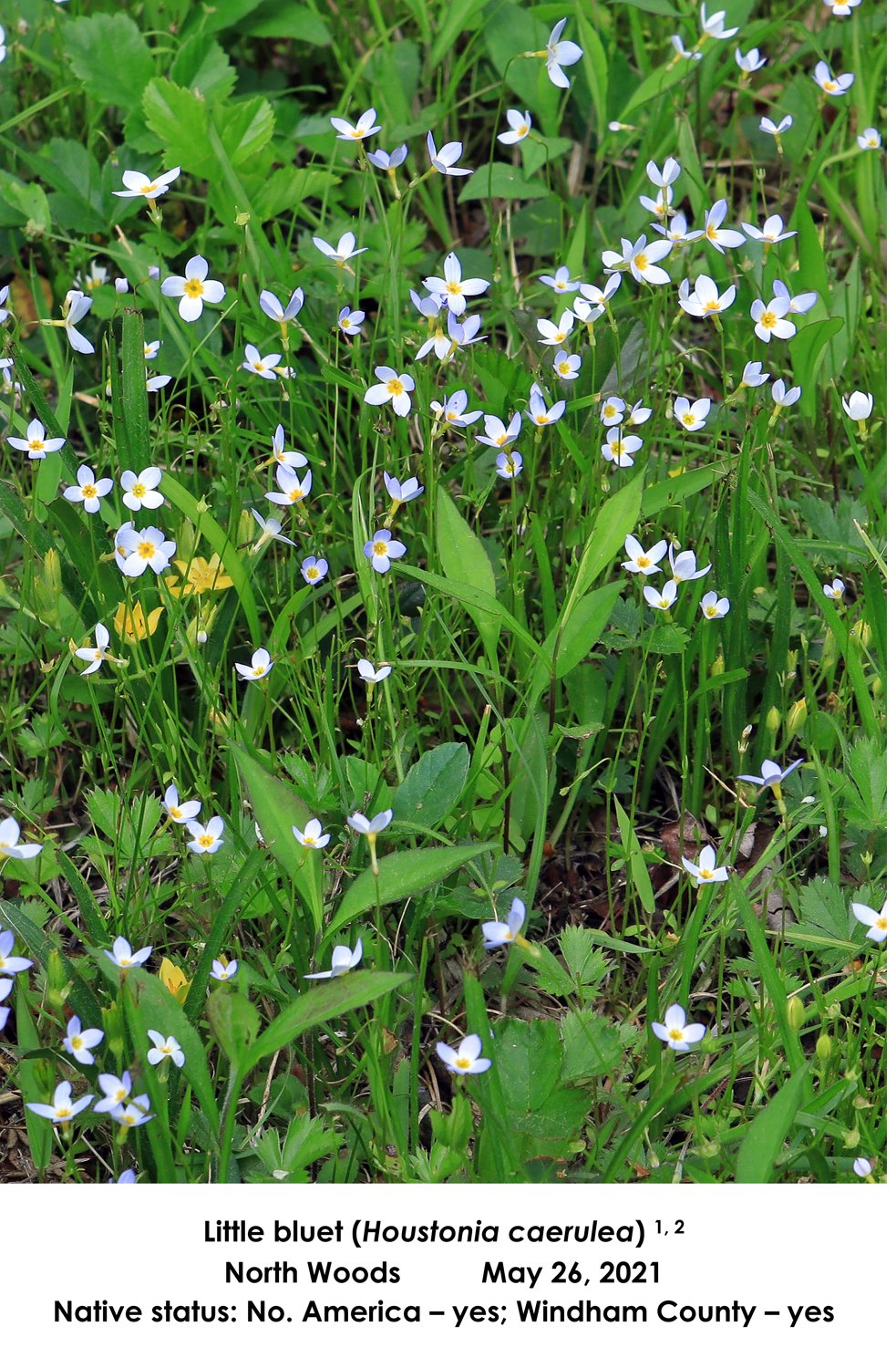

The major emphasis of this analysis is the photographic documentation of wildflowers that grow within each habitat. Seventy individual species are pictured here. Photo labels list currently accepted common and scientific names according to the website Go Botany (see below) and the locations where each plant was observed. The approximate sequence in which plants first bloomed is indicated by the dates on which they were photographed, understanding that some flowered between visitations, and that others may have been inadvertently overlooked on prior dates.

Each species’ native status in North America and in Windham County is noted, as reported by Go Botany. Species that are indigenous (native) to parts of North America, but that are non-native in other regions, whether introduced intentionally or unintentionally, are labeled “yes & no.” Such non-native species originated on other continents and were transported here in ships’ ballast, livestock feed and agricultural stock, among other sources. All species identified here as non-native have become naturalized. One meadow species is listed as invasive by the Connecticut Invasive Plant Working Group (CIPWG).

Finally, plants that Teale described in A Naturalist Buys an Old Farm, whether at the genus or species level, are identified by superscript 1 following their names. Those described in A Walk Through the Year are identified by superscript 2.

Plant identification is based on the following sources:

Digital applications: seek by iNaturalist; Picture This

Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide, Lawrence Newcomb, 1977.

A Field Guide to Wildflowers, Roger Tory Peterson and Margaret McKenny, 1968.

Go Botany: Native Plant Trust for New England, funded by the National Science Foundation.

Personal communication, Connecticut Dept. of Energy and Environmental Protection, Wildlife Div.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Following each of the habitat narratives below are photographs showing the changes from month to month in that habitat, and a gallery of the plants observed therein. The habitat photos may be advanced manually. The wildflower images will automatically cycle in chronological order according to the dates on which they were photographed.

The Lane

Edwin Teale placed special significance on the scenic farm lane that introduces visitors to Trail Wood, and that typifies the New England landscape he and Nellie so valued. The lane today retains the visual and ecological character that he wrote about. This project reflects some of his observations.

The lane becomes increasingly shaded between May and July as the surrounding trees leaf out and the bordering plants increase in height and mass. As Teale noted, due to the angle of the sun in spring and the presence of the sheltering stone wall on the south side of the lane, the north side is both sunnier and warmer. I witnessed several examples of the influence that those conditions have on the wildflowers growing there:

(1) the number of wildflower species blooming on the north side of the lane was twice that on the cooler, shaded south side, evidence of Teale’s observation that plants on the north bloom earlier than those on the south in response to that increased insolation;

(2) plants that produced colored blossoms occurred only on the north side of the lane. Only plants with white blossoms occurred on the south side, showing that plants with colored flowers are more adapted to grow in sunlight; and

(3) more species bloomed for the first time in May (10) than in either June (4) or the first half of July (4), showing further influence of sunlight, which was greatest in May, on wildflower blooming.

Teale wrote that while plant growth in any season depends on many interrelated and constantly varying environmental factors, including precipitation and temperature, wildflowers “…arrive in their appointed sequence.” Thus the flowering sequences shown in the dated photographs of plants growing on the lane likely follows the same general pattern from year to year. Flowering is timed to, among other things, enable plants to avoid competition with neighboring species as they grow, and to thereby ensure that they are accessible and visible to their respective pollinators.

The lane appears to be a woodland environment, yet none of the 39 wildflower species distributed between the lane and the Trail Wood forest occurred in both habitats. While this relationship may vary over the entirety of the growing season, my observations may reflect the fact that the lane is an engineered, and thus a disturbed, environment. According to Go Botany, 77% of the species photographed there are adapted to disturbance.

The majority (78%) of the wildflowers blooming on the lane during the project period were indigenous, or native, to parts or all of North America and to Windham County. None of those are considered invasive.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Meadows

As along the lane, the appearances of Monument Pasture, Firefly Meadow and the Starfield changed as the seasons advanced. Using Firefly Meadow as an example, monthly photographs show the plants in the meadow increasing in height and individual biomass, gradually circumscribing the pathway that bisects it. The profusion of wildflower blossoms shown in the accompanying photos attracts increasing numbers of pollinating insects, thus sustaining those plant populations for the future.

Unlike the lane habitat, where flowering patterns are governed by the varying availability of sunlight, the unsheltered meadow plants are exposed equally to solar radiation. While meadow species bloom sequentially, as shown in the dated photographs that follow, plants with white and colored blossoms grow side by side throughout the habitat.

The plant community in the meadow is distinct from those in the other Trail Wood habitats. Of the 49 species of wildflowers photographed between the lane and the meadows, only four were found in both habitats – and those grew principally in the transitional zone encompassing the sunnier western end of the lane and the partially shaded eastern edge of Firefly Meadow. No meadow species were found in the forest or in the wet habitats.

A factor that affects blooming is reproductive method. The plants growing on the lane as well as those in the forests and wet areas were all perennials, many having discreet and limited bloom times. By comparison, almost a quarter of the pictured meadow plants were annuals or biannuals that flower longer in order to most effectively disperse their seeds.

Teale described the Trail Wood meadows as “…fallow fields reclaimed by flowers…” The number of wildflower species photographed in the meadows far exceeded those in the other habitats. However, more than half of the observed meadow species were non-native to Windham County and to North America. While past agricultural practices likely enriched the meadow soils to the benefit of the plant community there, studies have shown that soil disturbance such as tillage also creates conditions that facilitate the establishment, and possibly feed into the long-term persistence, of fast-growing non-native species (Kyle, Beard and Kulmatiski, 2007)* like those at Trail Wood. One meadow species present during the residency period, spotted knapweed, is listed as invasive by CIPWG.

* Kyle, G.P., K.H. Beard, and A. Kulmatiski. 2007. Reduced soil compaction enhances establishment of non-native plant species. Plant Ecology (193):223-232.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Wetlands

Various wet habitats are present at Trail Wood, comprising both open water and wetland margins. The open water bodies have different histories. The Beaver Pond was created by those semiaquatic rodents from a swamp fed by Hampton Brook. The pond south of the farmhouse was mechanically excavated from a red-maple swamp and impounded by an engineered dam. Both share some of the same lacustrine species.

Hampton Brook rises in Natchaug State Forest to the west of Trail Wood. It bisects much of the sanctuary, and flows under the long lane before exiting the property to the south. The wetland margins include the banks of the brook, the shores of the ponds and the surrounding wet woods and swamps.

Gross seasonal transitions in wetland habitat were most visible at the Beaver Pond. Comparison of photographs taken in June and July show changes in the increased expanse of ferns and emergent plants along the southern shore. The trees surrounding the pond exhibit transformations that are seen elsewhere in the forests and along the lane, as their density and color changes. Summer foliage becomes darker than that of spring as trees produce bitter-tasting tannins to repel leaf-eating insects.

Interestingly, the Beaver Pond also provided an example of sudden and unexpected change during the course of this residency. A series of intense thunderstorms followed by a tropical storm in early summer caused Hampton Brook to surge and overfill the pond. The beaver dam that retains the pond breached on July 9, two days before my arrival at Trail Wood. The water level in the pond dropped by several feet, exposing the normally sub-surface entrances to the beaver lodge. The out-rushing pond water flooded the downstream woods and scoured the lane. Yet, within the week that followed, the beavers had substantially repaired the dam and the lodge entrances were again submerged.

Fewer flowering plants were observed in the wet areas than in the other habitats. All were native and none were invasive. Their flowering sequence is shown in the accompanying photographs.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Forest

The forest at Trail Wood comprises the majority, spatially, of the sanctuary, surrounding the other habitats that have been described. Edwin and Nellie Teale identified individual regions of the forest as the North, Far North, West and South Woods, and each is unique in their telling. Views into and through the forest change as the density and color of foliage vary with the season, as shown by the early May and late June photographs of the North Woods trail that leads through a stone wall to the Beaver Pond.

The wildflowers pictured here were located along the wooded roads and trails of the various forest regions. They flowered sequentially like their counterparts in the other Trail Wood habitats. Several species grew along the margins of comparatively wide, grassy trails like Old Woods Road. Others were found growing in leaf litter beside narrow Far North Woods paths.

Only one forest species, common selfheal, was found elsewhere at Trail Wood. Interestingly, the plant bloomed both on a steep grade along Old Colonial Road on Old Cabin Hill, and on the level, damp surface of the dam that retains the southern pond.

None of the wildflowers observed in the forest were non-native or invasive.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Photographs were taken using Canon R6 and 70D cameras with a 24-105/f4 L IS lens.